Ghost of 'Boss Hall' Haunts Green Cove Land Deal, Lawsuit

The 'Corrupt Son of a Bitch' Who Spawned a Political Dynasty

Imagine a Netflix series:

The scion of a corrupt political dynasty, backed by small-town politicians, defends her interests in a brutal legal battle against the local CIA “air force” base. The case involves multi-million-dollar development rights for a parcel of land that may well have been stolen.

This is a story about “corrupt son-of-a-bitch” Sheriff John Hall, his influencial son J.P. Hall Jr. and the scion herself, granddaughter Virginia Hall.

The sheriff and his son are long dead. It must be said upfront that nothing in this story implicates Virginia Hall in anything immoral, unethical or illegal. We no longer adhere to Old Testament notions of “punishing the children for the sins of their fathers to the third and fourth generation.”

But the lawyer for Pegasus Technologies, the CIA-connected aviation outfit, has said in open court that the City of Green Cove Springs bent the rules to benefit Virginia Hall when it simultaneously annexed a 14-acre parcel belonging the Hall family, rezoned it to allow residential uses and approved a 260-unit apartment complex.

Pegasus alleges that four-story buildings, in line with its runway at Reynolds Industrial Park, would create a safety hazard. A lawyer for Pegasus has argued that the city had failed to take into account safety and zoning best practices because of Virginia Hall’s political connections.

Reynolds Industrial Park joined its tenant Pegasus in the lawsuit in which Green Cove and the Hall family are co-defendants. The trial was held in Florida circuit court on July 6 and 7. Judge Don Lester is expected to rule by the end of August. Read earlier stories about the lawsuit.

Nothing in the public record suggests that Virginia Hall has been more than a minor player in local politics. She has served unremarkably on the Green Cove Springs City Council and the Orange Park Town Council. More noteworthy, perhaps, is her marriage to Mark Scruby, who served 27 years as Clay County Attorney before joining the Rogers Towers law firm in Jacksonville. 1

Though innocent of paternal sins, successive generations are not free from consequences altogether. If Virginia Hall indeed enjoys any kind of special status in Clay County, it must surely derive from the outsized roles played by her father and grandfather—public heroes in their day, less sympathetic in hindsight.

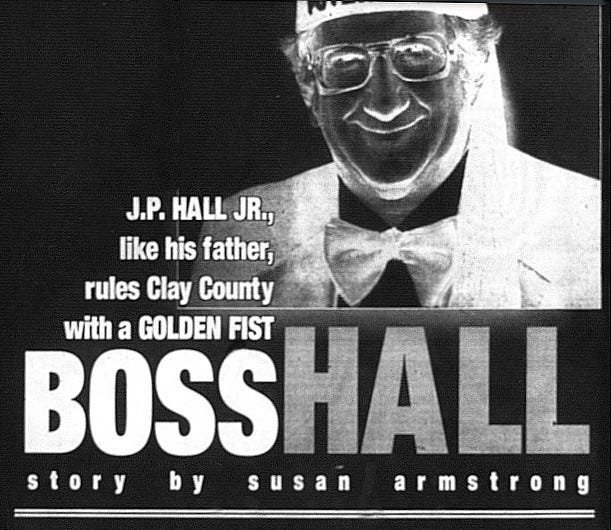

The shift in perception can be traced to Sept. 23, 1997 when Folio Weekly, Jacksonville’s alternative newspaper, published a hard-hitting story about the Halls that exposed what heretofore had existed only in Clay County’s repressed collective memory. No newspaper before had written anything but puffery about Clay’s tough-guy sheriff.

The author was no Yankee carpetbagger. Susan Armstrong is a native of rural Lousiana. Armstrong was a former Times-Union columnist and now writes for the online Florida Trident. In person, she is as Southern as sweet tea. She lives in Clay County.

Armstrong says her Folio story “Boss Hall” was based on interviews with as many as 50 Clay residents.

I talked to people who had been living here a long time. I talked to historians, and I talked to Sam Saunders who was John’s best friend. I talked to people who had lost their land, but maybe not directly. Their parents or grandparents had remembered losing their land. I talked to people who used to work in the county…

A lot of the people wanted to be off the record…Many were impacted by John Hall, and many were negatively impacted by J.P. Hall Jr.

About a month ago, Virginia Hall was provided with a copy of the “Boss Hall” story so she could comment. She has not replied to the email, but, if she changes her mind, her response will be published on this platform in full.

In June 2022, Hall stood before the Green Cove City Council arguing in favor of the development plan for the 14-acre parcel along Highway 17, south of the city.

“My grandfather actually started purchasing property in Clay County in 1928. So, I don't know exactly when this piece was acquired,” she told the council. “We still have a significant amount of property that is along (County Road) 209 and along (Highway) 16 that is adjacent to Reynolds, so we are impacted in several different ways by this.”

When the parcel was acquired is irrelevant—sometime during Hall’s 36 years as sheriff. And given the intervening decades, how the land was acquired no longer matters either, given that the ringleader is dead and the statute of limitations for criminal racketeering expired long ago.

Racketeer

Search for “J.P. Hall” and “deed” in the Clay County records and you will find dozens if not hundreds of entries going back decades. Armstrong’s Folio story suggests how a rural sheriff could amass a fortune while earning a modest county salary. Hall, she wrote, had seen the misfortunes facing Clay families during the Great Depression as opportunities. An online piece she wrote later on—“Who’s Afraid of Virginia Hall”— was more specific:

Sheriff Hall…chose land and homesites he wanted for his own, threatening the property owners with physical violence and jail if they paid their taxes. When the owners lost their properties due to foreclosure, he bought them for a pittance. As sheriff for 36 years, Hall decided who ran for office, who was elected and who kept their jobs.

In the same story, Armstrong wrote about how Hall also ran protection rackets, taking cash from the county’s whisky bootleggers and bolita2 gambling organizers.

In “Boss Hall,” Armstrong wrote that the sheriff once threatened a member of a prominent Clay family with bodily harm if he did not join the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan.

Asked about it recently, Armstrong says she got that anectdote interviewing a close relative of the man who was threatened. She says her Folio story actually understated Sheriff Hall’s role in the Klan and Clay County’s racially troubled past. For at least part of his time in office, she says, Clay was a “sunset county,” and Hall was the enforcer.3

“The KKK was really big down in Middleburg and Green Cove, and he was a big part of it,” Armstrong says. “It was very well known that in Clay County, if you were black, you could not be here after dark. You could come here during the day and work, but you had to cross over the bridge, or get out of the county when the sun went down.”

At some point, Sheriff Hall acquired a controlling interest in the Green Cove Springs Bank. He helped found the Florida Sheriff’s Association, and, as the wealthiest sheriff in the state, came to control that institution and contributed to chosen candidates for sheriff throughout the state. Add to that whatever his role was in the KKK, and Hall had his hands on almost every local lever of power.

Some people fought back, however.

How the Green Cove Police Came To Be

In case anyone was wondering why Green Cove Springs has its own police department, when the Sheriff’s Office resides within the city limits, Armstrong’s “Boss Hall” provides the answer.

When World War II veteran Arthur Frederick Rivers returned to Green Cove Springs in 1946, he was shocked to see his hometown in the tight grasp of Sheriff Hall. “There was nothing that went on the county that John Hall didn’t know about, or was part of,” said Rivers, now 77. “He was a corrupt son-of-a-bitch.”…

A covert campaign was launched among black and white residents in Green Cove Springs to get Rivers elected to the city commission and then appointed as major.

Rivers was elected. According to Armstrong’s “Boss Hall,” the sheriff tried bullying Mayor Rivers but failed to stop him from establishing the independent police force that Green Cove has today.

Rivers’ team also prevailed in a turf war over the Sheriff’s Department habit of arresting sailors on liberty from the Navy Base, even though the arrests were happening within city limits and therefore outside county jurisdiction. Hall’s deputies, as it happens, were being paid based on how many arrests they made. At the request of the Navy, Green Cove made them stop.

J.P. Hall Jr.

Hall’s son J.P. Hall Jr. never held public office, but, according to Armstrong, he continued to exercise nearly the same power as his father behind the scenes, choosing candidates for office, making decisions on hiring and firing within county government and generally “making his political wishes known.”

He cultivated a reputation as a philanthropist by founding non-profits such as J.P. Hall Children’s Charities, which is now run by Virginia Hall and her husband. A lot of local folks appreciate the work done by the charity. But Rivers, interviewed late in life, told Armstrong that the charities were really an attempt at reputation laundering on J.P. Hall Jr.’s part.

He has those charities because he wants everybody to forget what his daddy did to this county. I guess if you’ve got enough money, you can buy yourself a favorable place in history.

Rogers Towers represents the Hall family in the Pegasus lawsuit.

According to Wikipedia: Bolita was brought to Tampa, Florida, in the 1880s, and flourished in Ybor City's many Latin saloons. Though the game was illegal in Florida, thousands of dollars in bribes to politicians and law enforcement officials kept the game running out in the open…In the basic bolita game, 100 small numbered balls are placed into a bag and mixed thoroughly, and bets are taken on which number will be drawn.

After the Civil War, Clay County was the scene of a terrible incident involving a family of former slaves that purchased land from a local farmer. The farmer tried to renege on the deal and when the family refused to leave, the Ku Klux Klan flogged the father, raped his wife, crippled their infant son and tore down their house. This report to Congress on the incident is from Clay County Archives:

Always wondered how a civil servant could be so wealthy and powerful.