Schooner America's Second Act Was as Lively as Her First

Famous Yacht Was Scuttled by Confederates at Dunns Creek Near Satsuma

Nowadays, the race for the America’s Cup looks like science fiction with “flying monohulls” skimming along at 50 knots, hoisted by foils above the aqueous friction. It is a sign of how far we’ve come, however, that the original America, after which the race was named, inspired similar awe when in 1851 the Yankee schooner humbled Britain’s fastest yachts in a race attended by Queen Victoria.

Who came in second, she asked? “There is no second, your majesty.”

The answer was a characteristically British characterization of a blow-out. Had the Queen asked, “What now for America?” the Future might have whispered in her ear, “Honey, you ain’t seen nuthin’ yet.”

America had a second act, and it would be a far wilder ride than her first, albeit little remembered.

Red’s Wine Bar, Green Cove Springs, Florida

“Why don’t we take one of your boats to where they scuttled the America,” I asked the guy on the next barstool. Peter Kyne’s company shoots off fireworks all over North Florida from a fleet of pontoon barges. “The Confederates sunk her in Dunn’s Creek to keep her out of Union hands, and I think I know the exact spot.”

Soon after in August 2021, we ventured out, like Simon and Garfunkel, to look for America. We launched one of Kyne’s barges into the St. John’s River and set a course for Dunn’s. It was only after we reached the spot—a 180-degree switchback in the creek, close to it’s source at Crescent Lake—that Kyne came to the realization that America wasn’t actually there anymore—her scuttling was just a chapter in a history that would continue for another 80 years.

Hilarious. I didn’t mislead the guy on purpose, and I was flattered that he had thought that I might possess secret knowledge about a famous yacht’s final resting place. We chalked it up to the kind of miscommunication that happens when plans are made at bars late in the evening. Me, I just wanted a ride to check some depths and grab a few photographs, like this one:

Toy for British Aristocrats

So what brought America from the Isle of Wight to Dunn’s Creek, and what happened afterward?

Ten days after winning the race around Isle of Wight and securing the Cup for the New York Yacht Club, America’s ownership syndicate sold her to a British noble for 5,000 pounds. Lord John de Blaquiere cruised her a bit and celebrated when a letter later arrived from the United States disclosing the location of two dozen bottles of very, very expensive wine hidden aboard and informing his lordship that he was free to dispose of this treasure as he saw fit.

de Blaquiere then went on to race her a bit, too, but in 1853 he sold her to another nobleman named Henry Templetown, a collector of yachts who spent the season shifting among the various yacht clubs to which he belonged. He hardly used America and let her deteriorate at her berth before selling her to a shipbuilder for next to nothing in 1858.

Henry Southerby Pitcher restored the boat to her former excellence but managed to lose the distinctive eagle that graced America’s transom. The carving was later found serving as a sign on Isle of Wight for a tavern named “The Eagle,” which remained in business until the late 1960s.

And Now the Story Gets Interesting

Pitcher sold America to an enigmatic character who called himself Henry Edward Decie—some of the time. No record of Decie exists before he re-registered he vessel as Camilla in 1860 and no one has found any mention of him whatsoever after the final year of the American Civil War.

Perhaps the most thorough account of America’s history comes from a prolific writer-researcher who worked in the latter half of the 20th century. In his book “The America: the Story of the World’s Most Famous Yacht,”

Charles Boswell described Decie thus:

On one side of the Atlantic or the other, in print or in longhand, his name was spelled nine additional different was: Dacie, Dacier, Dacy, Deacie, Deacy, Deasy, Decey and Decri. Also, while usually addressed as “Mister,” he was often called “Captain,” and on at least one occasion…was referred to as “Lord Dacy”…

Just as Decie’s name had never appeared in the yachting press prior to 1860 it did not appear again after 1864. Taking as gospel the assumption that Henry Edward Decie as not the mysterious mariner’s real name, nautical historians have spent more than a century fretting over his true identity. Actually it matters little. All that matters is that for a brief while in the long career of the yacht America, the “courteous” yet “careless” man known as Decie sailed her three times across the Atlantic with interesting objectives.

Decie and Camilla disappeared from view for eight months after the purchase, he claiming to have voyaged to the West Indies, although there was no proof of that (and moreover, he had a habit of misinforming customs officers of his prior whereabouts). What is known is that Camilla arrived at Savannah on April 25, 1861, 13 days after the start of the Civil War.

Within weeks, the Confederacy had purchased Camilla, and short of everything to fight a war, including naval officers, had pursuaded Decie to remain in command. He had apparently represented himself as a former British navy captain. The Rebel government paid Decie $26,000 dollars for Camilla—about $900,000 today—and an additional $6,000 to equip and provision her for a first mission.

On May 21, 1861, Camilla got underway for Ireland, carrying as passengers Decie’s wife and child and Confederate agents whose mission was to secure construction slots for two ironclad warships in England or France and to root out a possibly disloyal Confederate representative already there. The schooner flew the Union Jack, but Union spies were able to deduce the truth and issued an APB.

On October 25, 1861, Camilla returned to Dixie, arriving at Jacksonville, Florida, and there she accomplished…maybe nothing. As Boswell wrote:

A publication of he Florida Historical Society of many years ago declared that the vessel then became a blockade runner and mde “flying trips to Nassau and Bermuda.” Confederate Customs records indicate, however, that if such voyages were made they were limited to two. The yacht was out of the port once in December 1861, returned in early January the year following and then quickly out and in later in January.

That last return to the St. John’s River was a dramatic one, according to the description by an eyewitness:

One moonlight night at Mayport, when the Federal gunboats were just far enough outside for the black hlls to be faintly visible, there came up out of the east on a wholesale sailing breeze a yacht with ever stitch of canvass set and drawing. The was cut from her bows like a knife would do it and was thrown high over her deck an on her sails. There came a flash and a boom from a gunboat, and a shot crossed over her bow, followed by more flashes and shots, but on the gallant craft came, spar and rigging untouched, heeling over now and then and righting her self gracefully.

Running the blockade that night was described by Boswell as “the last advantageous use of the Camilla as a Confederate vessel.” (Other accounts claim that she had been renamed Memphis during her Confederate service, probably not.)

Trapped, Then Scuttled

At some point before March 11, 1862, Camilla’s name had been changed back to America. On that night, U.S. Navy warships steamed up the St. John’s River and took Jacksonville without firing a shot. Frightened local officials quickly volunteered that the steamship St. Mary’s and America had slipped their moorings and headed south on the river the night before, with America most likely under tow. Retreating Confederate forces had also burned a ship under construction, seven sawmills, two iron foundries and a railroad depot.

A hotshot young Confederate officer named Charles Hemming is widely credited with having led the scuttling expedition. A fellow soldier once described him as “an accomplished boatman.”

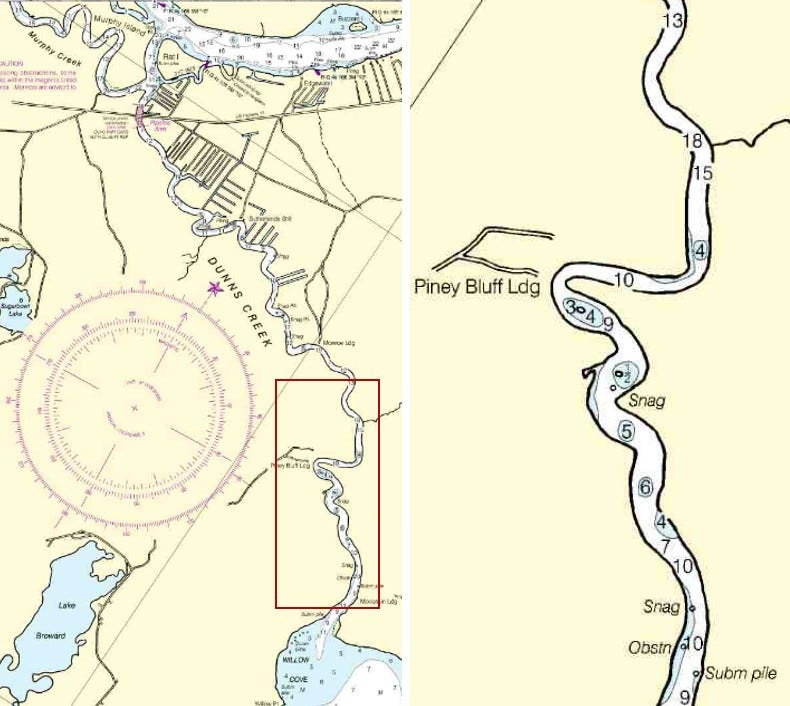

Dunn’s Creek connects the St. John’s River to Crescent Lake, the third largest in Florida. Hemming’s expedition sunk America about 70 miles south of Jacksonville by water. Her topmasts had been removed, but it was reported that she had been sunk along the creek bank in such a way that only her port rail showed above water. That makes sense for a 23-foot beam in 20 feet of water.

America’s draft was just over 10 feet, and, having piloted trawlers through Dunn’s creek several times, I can only imagine the difficulties the Confederate crew must have had making the tow, as suggested in the charts below. The shoal-draft steamer St. Mary’s was also scuttled about 12 miles further along in another creek at the southern end of Crescent (called Dunn’s Lake at the time).

A career U.S. Navy lieutenant named Thomas Stevens was in charge of the Jacksonville incursion. He and his fleet commander made capturing America a priority, and, according to Boswell, were “almost boyish in their enthusiasm” to take what may well have been the world’s most famous yacht. But where was she?

The Confederates launched a disinformation campaign, spreading the falsehood that America had been scuttled at Black Creek about 50 miles north of Dunn’s. Accounts from later in the 19th century continued to name Black Creek in the America story in what today would be considered “blowback,” defined as disinformation that persists among an unintended audience.

In any event, the intended audience was not fooled for very long.

Florida was an information sieve for Union intelligence-gathering. Sources of information included slaves, Native Americans and growing bands of Confederate deserters. Ordinary Floridians were beginning to go hungry by 1862, and many would have gladly provided information for a pound of bacon. And, then as now, many residents had recently moved down from the north and secretly owed allegiance to the Union.

Stevens led a small fleet of gunboats up the St. John’s and was almost immediately rewarded with the information he needed to find America. He found the yacht up Dunn’s Creek just as his informant had promised. Stevens sent back to Jacksonville for the gear required to raise a 100-footer displacing more than 170 tons.

‘Adventurous Enthusiasm‘

Working with what one author called “adventurous enthusiasm,” Yankee sailors applied themselves to the task. First, they tried to improvise a travel lift by rigging a sling from three trees on the riverbank, under the boat to a gunboat alongside, the Darlington. They tried for a week to gain purchase, eventually snapping the trees.

An article from an 1872 edition of Aquatic Monthly magazine recounts what happened next:

Just as it looked as if the yacht must be abandoned, one of the pickets bought in a lengthy specimen of Florida backwoodsman, who said he was present when the yacht was sunk and that she was scuttled by three two-inch holes bored forward and two aft.

Upon this information a mate from the Wabash and another mechanic made three rought pumps from pine boards, 13 feet long and flumed the two square haches on the after deck of the America until they were six above the water of the creek…Putting a pump down each flume, with four ment to each pump, water ws thrown out so muc quicker than…would make it through the five auger holes that she commenced rising at once.

Even if the hoists were not able to raise America, my assumption is that the effort had managed to level her off enough so those hatch openings were pointing upward. I find it puzzling that tall guy’s news about the holes should have been inspiration to try the pumps. Presumably, they could have applied this idea earlier, given that they didn’t bother to plug the five holes until after most of the water had been pumped out.

Long story short: America’s internal ballast was transfered to the largest gunboat, and thus lightened, the barely damaged vessel was towed back to Jacksonville.

Meanwhile, according to Boswell, a resident of the nearby town of Palatka was being blamed for providing Stevens with America’s whereabouts. The man, identified only as DeCosta, was accused of being a Union collaborator. He was arrested and reportedly held by the owner of a local grain-grinding business at Orange Mills, a few miles north of Dunn’s Creek along the St. John’s.

Stevens gave the mill’s owner, Dr. R. G. Mays, a deadline to turn DeCosta over to the federals. When Mays failed to produce his prisoner, the Union Navy shelled Orange Mills, destroying its buildings. Of DeCosta’s fate there was no mention.

Ship of the U.S. Navy, Then Ben Butler’s

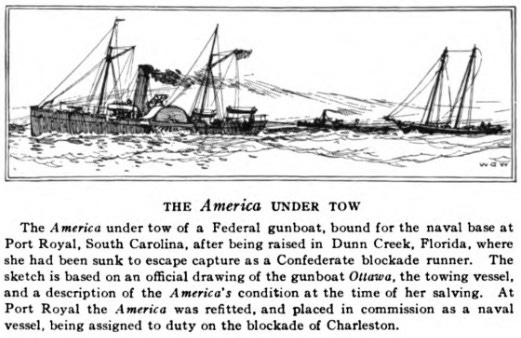

In April 1862, America was towed to Port Royal, South Carolina, which had recently been taken by the Union, where she was refit and put into service, first as a dispatch-runner, then as an armed blockader with a crew of 27, patrolling off Charleston. In October she nabbed the small blockade-runner Davy Crockett with a cargo naval stores—rosin and turpentine—bound for Bermuda.

After participating in several successful engagements in 1863, America was dispatched to serve as a training ship for the U.S. Naval Academy, which had moved its operations from Annapolis to Newport, Rhode Island for he duration of he war. En route, having been crewed by midshipmen, she was redirected to participate in the hunt for a notorious Confederate privateer.

After the war, one of its most colorful soldiers and later a congressman, Major General Ben Butler of Massachusetts, managed to acquireAmerica as his personal yacht through chickanery. In June 1873, Butler bought America at auction using the services of a straw buyer for $5,000. The sale had been rigged, and later became the subject of a Congressional investigation, which changed nothing.

The Navy got a small measure of revenge. When Butler’s crew arrived at Annapolis to take possession of the yacht, they found the internal ballast had been removed with Academy officials claiming that the valuable lead ingots had not been part of the deal. Butler connived to get his lead anyway, and a shady deal was struck with the Boston Navy Yard, which supplied the bars at taxpayer expense.

Crappy military leader and devious politician nothwithstanding, Butler proved an excellent ship’s husband for the famous yacht. He had her overhauled twice, the first time by Don McKay, the famed builder of clipper ships. He raced America with fervor, and occassionally his opponents were also political rivals, men he hated.

After Butler’s death in 1893, America languished at the dock, and in 1897 Butler’s son gave her away to another Massachusetts politician named Butler Ames, who sold her to Massachusetts banker Charles Foster in 1917, who sold her to the America Restoration Fund in 1921, which donated her back to the U.S. Naval Academy, which assigned her the designation IX-41.

The Navy, however, failed to maintain her and, belatedly in 1941, she was a hauled out at the Annapolis Yacht Yard for some work. Her stern hogged several inches on the railway. Work began on America, but after Pearl Harbor she was all but forgotten as the yard turned to building torpedo boats for the war.

On Sunday, March 29, 1942, a blizzard struck Annapolis, dropping up to three feet of snow on her brick streets and collapsing the shed that housed America.

Her run was over.Americawas destroyed 91 years after her launch. Officially, though, she was one of only three commissioned Navy Ships in service during both the Civil War and World War II, the others being theUSS ConstitutionandUSS Constellation.

Postscript

Scuttler-in-Chief Charles Hemming went on to have an illustrious life. He was captured by Union forces during a battle in Tennessee, escaped from his prison camp, fled to Canada and conducted guerrilla raids into upstate New York, took a steamer to Cuba and snuck back Jacksonville just before the war ended after being lowered into a dinghy from a blockade runner.

The Union, as it happened, was very, very good to Hemming after the war. He became wealthy as a Colorado banker, and in 1899 donated a 62-foot-high Confederate monument, costing $20,000, to the city of Jacksonville, which was erected at Hemming Park. Two years ago, as part of the anti-Confederate-statuary movement, the monument was taken down and returned to Hemming’s descendants and the park renamed.

Thomas Stevens, who undid Hemming’s work at Dunn’s Creek, was rewarded for his competence throughout the war with promotion to admiral. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. A World War II destroyer was named after him.

About Henry Decie: I would have liked to imagine he was some kind of time-traveler, like a character in the “Outlander” series, maybe a sailor of the future who became bored with his “flying mono-hull” and wanted to experience the grit and grind of 19th century sailing and blockade warfare.

Alas, even as fantasy this scenario won’t hold up. Decie’s last documented act was to take money from gullible Confederate investors hoping to fund another gunboat from England—this just weeks before Lee’s surrender. Nobody with the ability to move through time would have the slightest need for 19th century gold.